| Contact: David Bricker

brickerd@indiana.edu 812-856-9035 Indiana University

BLOOMINGTON, Ind. -- To make large sheets of carbon available for light

collection, Indiana University Bloomington chemists have devised an unusual

solution -- attach what amounts to a 3-D bramble patch to each side of

the carbon sheet. Using that method, the scientists say they were able

to dissolve sheets containing as many as 168 carbon atoms, a first.

(suite)

|

suite:

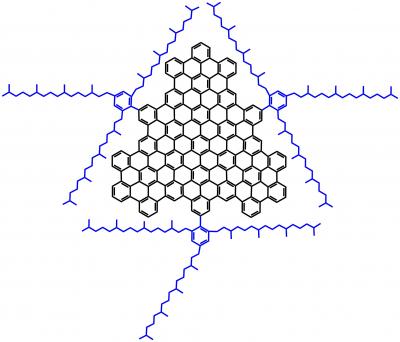

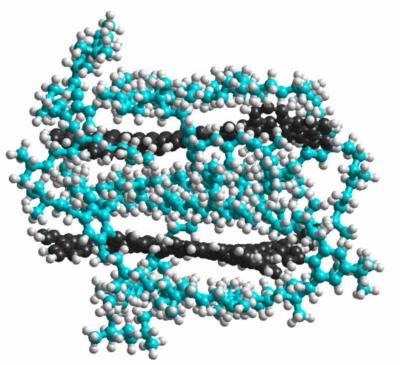

Unfortunately, scientists find large sheets of graphene difficult to work with, and their sizes even harder to control. The bigger the graphene sheet, the stickier it is, making it more likely to attract and glom onto other graphene sheets. Multiple layers of graphene may be good for taking notes, but they also prevent electricity. Chemists and engineers experimenting with graphene have come up with a whole host of strategies for keeping single graphene sheets separate. The most effective solution prior to the Nano Letters paper has been breaking up graphite (top-down) into sheets and wrap polymers around them to make them isolated from one another. But this makes graphene sheets with random sizes that are too large for light absorption for solar cells. Li and his collaborators tried a different idea. By attaching a semi-rigid, semi-flexible, three-dimensional sidegroup to the sides of the graphene, they were able to keep graphene sheets as big as 168 carbon atoms from adhering to one another. With this method, they could make the graphene sheets from smaller molecules (bottom-up) so that they are uniform in size. To the scientists' knowledge, it is the biggest stable graphene sheet ever made with the bottom-up approach. The sidegroup consists of a hexagonal carbon ring and three long, barbed tails made of carbon and hydrogen. Because the graphene sheet is rigid, the sidegroup ring is forced to rotate about 90 degrees relative to the plane of the graphene. The three brambly tails are free to whip about, but two of them will tend to enclose the graphene sheet to which they are attached. The tails don't merely act as a cage, however. They also serve as a handle for the organic solvent so that the entire structure can be dissolved. Li and his colleagues were able to dissolve 30 mg of the species per 30 mL of solvent. "In this paper, we found a new way to make graphene soluble," Li said. "This is just as important as the relatively large size of the graphene itself." To test the effectiveness of their graphene light acceptor, the scientists constructed rudimentary solar cells using titanium dioxide as an electron acceptor. The scientists were able to achieve a 200-microampere-per-square-cm current density and an open-circuit voltage of 0.48 volts. The graphene sheets absorbed a significant amount of light in the visible to near-infrared range (200 to 900 nm or so) with peak absorption occurring at 591 nm. The scientists are in the process of redesigning the graphene sheets with sticky ends that bind to titanium dioxide, which will improve the efficiency of the solar cells. "Harvesting energy from the sun is a prerequisite step," Li said. "How to turn the energy into electricity is the next. We think we have a good start." PhD students Xin Yan and Xiao Cui and postdoctoral fellow Binsong Li also contributed to this research. It was funded by grants from the National Science Foundation and the American Chemical Society Petroleum Research Fund. To speak with Liang-shi Li, please contact David Bricker, University Communciations, at 812-856-9035 or brickerd@indiana.edu. "Large, Solution-Processable Graphene Quantum Dots as Light Absorbers for Photovoltaics," Nano Letters (Articles ASAP) |